european network for alternative thinking and political dialogue

30 April 2024

26 April 2024

28 April 2024

Marseille event

The European Common Space for Alternatives (ECSA)

24 April 2024

ILS LECTURE SERIES 2024 – INTELLECTUALS

Una Blagojević: Intellectuals in Yugoslav Socialism – Critique and Philosophy

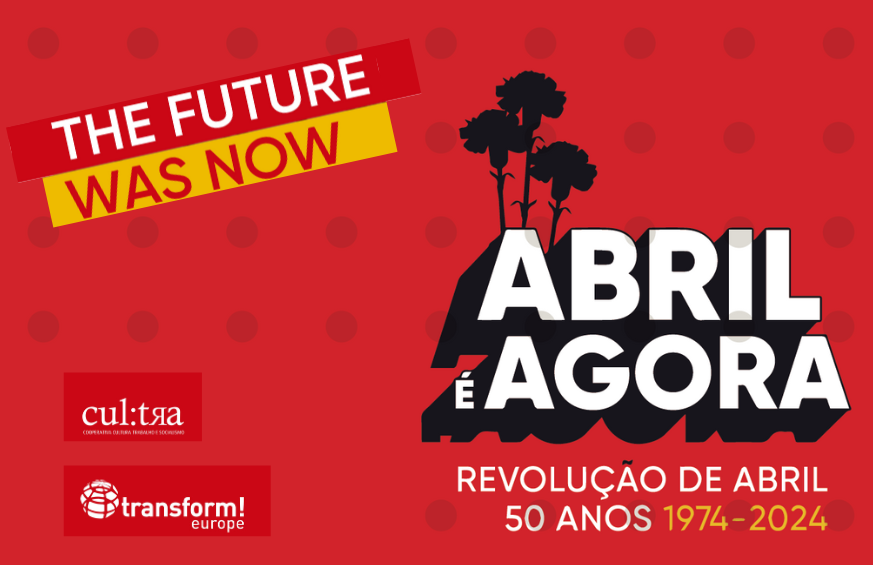

The Party of the European Left, Bloco de Esquerda & transform! organise the 4th edition of...