european network for alternative thinking and political dialogue

30 April 2024

26 April 2024

28 April 2024

24 April 2024

ILS LECTURE SERIES 2024 – INTELLECTUALS

Una Blagojević: Intellectuals in Yugoslav Socialism – Critique and Philosophy

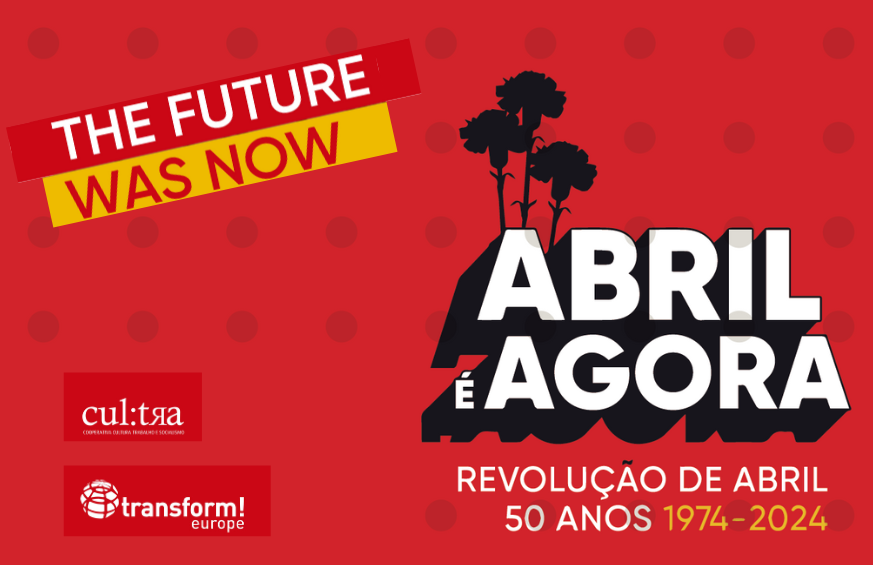

The Party of the European Left, Bloco de Esquerda & transform! organise the 4th edition of...