On 20 March 2019 provincial elections took place in the Netherlands – with significant consequences.

Since the provincial representatives elect the members of the Dutch upper house, the Senate, provincial elections have direct repercussions for national politics. The recent elections were won by the Forum voor Democratie (FvD) (Forum for Democracy). This newcomer grew out of a think tank established in 2015 by Thierry Baudet (1983). A young conservative intellectual with the public image of a dandy, Baudet gained prominence as one of the initiators of the April 2016 Dutch referendum on the EU Association Agreement with Ukraine. At the time, Baudet acted in concert with several other populist initiatives of the right that shared his EU-sceptic agenda. In September 2016 Baudet together with Henk Otten turned his think tank into a political party with a Eurosceptic, anti-immigration and climate-sceptic program. The party appeals by a mix of populism (criticizing the Netherlands’ ‘ruling elites’, their ‘party cartel’ and ‘job carrousel’) and romantic nationalism.

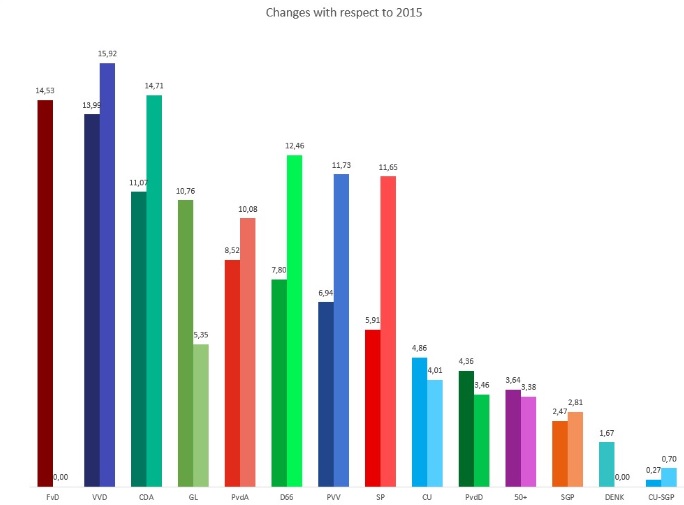

Upon its establishment, FvD obtained 1,8% of the votes (and thereby 2 seats) in the national elections of March 2017; in the March 2018 local elections it won three seats (5,7%) in the municipal council of Amsterdam (the only place where it fielded candidates). Since then, FvD has seen a dramatic rise in support: in the recent provincial elections, the party won over 14% percent of the votes, and gained 13 seats in the Senate (out of 75). In one sweep, the newcomer became the Senate’s biggest party.[1] If we add the 6.9% of Geert Wilders’ PVV (Partij voor de Vrijheid/ Party for Freedom), this was the highest vote percentage that populist radical right parties ever obtained in nation-wide elections in the Netherlands.[2] Remarkably, FvD scored well in all provinces of the country.

At the same time, the elections showed a further fragmentation of the already very divided political landscape, which is increasingly populated by parties that claim to represent specific interest groups rather than broad political ideologies (newcomers to the parliament in the past two decades included a party for the elderly [called 50+], the ‘Party for Animals’, and the migrant party Denk, which is mainly focused on people from Turkish decent). The elections moreover confirmed the continued shift towards the right: as in the 2017 national elections, the victory of the Greens (GroenLinks, total 10,7%) did not compensate for the losses of the Socialist Party (now 5,9%) and the social democratic PvdA.

source: Wikipedia;

FvD: Forum for Democracy, European affiliation: ECR; VVD: People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy, ALDE; CDA: Christian Democratic Appeal, EPP; GL: GreenLeft, Greens; PvdA: Labour Party, S&D; D66: Democrats 66, ALDE; PVV: Party for Freedom, none; SP: Socialist Party, GUE/NGL; CU: Christian Union, ECR; PvdD: Party for the Animals, GUE/NGL; 50+, none; SGP: Reformed Political Party, ECR; DENK, none; CU-SGP: combined list in the North Brabant province;

Forum voor Democratie

Baudet places himself in the populist tradition of Pim Fortuyn, whose Lijst Pim Fortuyn (LPF) first entered the 2002 parliamentary elections and immediately obtained 17% of the votes. Fortuyn’s program altered the traditional radical right repertoire by focusing the anti-foreigner agenda specifically on Muslims. Fortuyn claimed to represent ‘the people’ against the ‘ideologically backward Islam’, but also against the ‘multicultural elite’ of the Netherlands that fostered ‘foreign threats’ – in particular immigration and supranational bodies (EU). The assassination of Fortuyn in the run-up to the 2002 national elections contributed to the idea of a harsh political struggle between the newcomers and the elites, and between left and right.

After losing its front man, the LPF fell apart due to internal discord, and by 2006 it had lost all its seats in parliament. Yet by that time, new initiatives on the right had sprung up. These included Geert Wilders’ Partij voor de Vrijheid (PVV), which positioned itself as staunchly anti-Islamic and for the ‘common Dutchman’. This is the Dutch tradition of populism in which Baudet’s Forum voor Democratie is rooted.

‘Democratic renewal’ and Neoliberalism

Forum voor Democratie advocates reforms of the political system as a means to overthrow the current political and cultural elites. This, so the FvD, is necessary because the elites are acting against the interests of the people. They do so out of loathing for their own (western) culture, a condition that Baudet likes to refer to as ‘oikophobia’. This ‘oikophobia’ ostensibly causes the elites to weaken the Dutch society – inevitably leading to its decline. In particular, ‘mass immigration’, European integration, and any agenda to prevent further climate change are depicted as schemes of the elites against the people. Thus, the party strongly opposes the Paris Accords and argues against an energy transition, which it claims will only weaken the Dutch economy.

From this follows that the elites need to be overthrown. And this, so the FvD, can best be reached through a process of ‘democratic renewal’ that brings politics closer to the people, away from party structures. Here the favorite catch words are e-democracy, open applications for public functions, digital voting in parliament, and referenda. In this aspect, the party claims to have been inspired by the Five Star Movement in Italy.

The overthrow of elites through more political competition is moreover linked to a neoliberal economic and political program. Sectors like healthcare and education should be improved through ‘healthy competition and decentralization’,[3] that is, by further privatization. And this again is linked to the idea that such public and semi-public sectors, along with the elites, are currently ‘too leftist’. Only days after the provincial elections, the FvD opened a "hotline" against "indoctrination in our education system", inviting pupils and students to film the acts of ‘left indoctrination’ that their teachers commit at schools.[4]

Political and cultural renaissance – by new elites

While Wilders poses as a common man, Baudet’s attack on the established elites goes hand in hand with his own elitism; at one point he called himself "the most important intellectual of the Netherlands."[5] The party’s attack on the ‘cultural elites’ of the contemporary Netherlands is furthermore sold as a defense of earlier European (rather than solely Dutch) culture – ideally of before the French Revolution. The party therefore sees no contradiction in advocating the return to a uniquely Dutch identity by copying examples of other western countries, including Finish education, the Swiss political system, and Australian asylum policies. Baudet claims to be an advocate of ‘traditionalism’, the broad spectrum of esoteric thinking from René Guenon to Alexander Dugin.

One of the main questions for the moment is if the FvD will be able to cooperate with other political parties – and how such cooperation will be received by FvD voters. The decline in votes for the PVV has in part been explained by Wilders’ rejection of taking on governing responsibility.[6] At the same time, participating in coalition governments inevitably means that the FvD will have to cooperate with the elites it claims to despise so much.

Revolutionary conservatism and the extreme right

While ‘cultured’ in his appearance, Baudet goes further than Wilders in promoting white identity politics. On many occasions, he openly flirted with the extreme right, agreeing with some of their standpoints and using their rhetoric. Into this category fall his anti-feminist statements and his promise of the rebirth of the nation under the leadership of a new elite. His interest in Oswald Spengler (1880-1936) and other revolutionary conservative thinkers is reflected in his doomsday vision of the Netherlands’ cultural and societal suicide, combined with the image of a decisive struggle for the continuation of western civilization. He uses terms that have specific significance for the extreme right – such as a reference to a ‘boreal Europe’ in his victory speech of 20 March. Many observers interpreted this as a dog whistle for right extremist supporters, for whom the term ‘boreal Europe’ signifies a white Europe. There is a fine line between this rhetoric and violence: when in December 2015 an angry mob stormed the town hall of Geldermalsen to protest against the housing of refugees in the municipality, Baudet legitimated this as the people’s "self-defense" against the "desktop murder" of the Dutch population by the government.[7]

Voters

Whom does this agenda attract? FvD voters are predominantly male (64%) and slightly older than average, with little trust in politics. Yet it would be a mistake to conclude that the party has no success with other groups: the FvD is the fastest growing political organization in the Netherlands. In January 2019, the party claimed over 30.000 members, including 4.000 members of its youth division. Although its voters are slightly lower educated that the average Dutch voters (47% of FvD voters have vocational education), the FvD has also had considerable more success in attracting voters with a higher education (29%)[8] than most European radical right parties, including the Dutch PVV.

In the latest elections, FvD won votes primarily from the PVV (31% of the current FvD voters had voted for the PVV in 2017), but also from governing parties, in particular the VVD (Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie, People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy) (affiliated to the European ALDE party) of Prime Minister Rutte (15%) as well as the Christian-conservative CDA (Christen-Democratisch Appèl, Christian-Democratic Appeal, affiliated to the EPP) (10%).[9] In a nutshell, for many FvD voters the VVD is not tough enough on the EU and immigration, whereas the PVV appears too radical. Moreover, 61% of those who voted for the Forum in 2017 did so again in 2019: in the highly volatile Dutch political landscape, this is the highest number of loyal voters of all parties.[10] 64% of those who voted for the FvD in the provincial elections of 2019 did so because of the party’s positions on national politics; only 28% said to base their vote primarily on the FvD’s provincial program.[11]

FvD voters moreover show affinity with strong male leaders such as Putin – akin to the alt-right in the US.[12] Opinion polls from the 2019 elections show that PVV and FvD voters are very much alike in issues of Euroscepticism, migration, and mistrust of national politics, with FvD supporters being slightly higher educated. As PVV voters are divided on the issue of climate change, the FvD can position itself as the party more strongly resisting any anti-climate change agreements.[13] The difference between PVV and FvD was, from the onset, primarily one of style. Before establishing his own party, Baudet repeatedly stated his support for Wilders, and there were even attempts to initiate political cooperation. The overlap in political program and in voters therefore is no surprise. In contrast to the PVV, the FvD was structured as a membership party, and its leader coquettishly stresses his PhD and his dandyish lifestyle. In this sense, Baudet is more a copy of the colorful Pim Fortuyn than of the dry and monodimensional Wilders. Fortuyn’s former driver Hans Smolders, now elected into the provincial parliament of Noord-Brabant for the FvD, claims that "Thierry finishes Pim’s work."[14] Baudet’s carefully cultivated image of an intellectual dandy has also contributed to the image of the FvD as a ‘more civilized’ variant of the PVV – a doubtful vision in the light of Baudet’s actual statements. Unlike the PVV, FvD is not anti-elitist per se. Instead, Baudet wants to replace the current elites with a new elite – namely, that of the party itself.

Please find the full-version on the right (pdf).

Notes

[1] The Dutch political system is characterized by a rather large number of parties, due to the absence of an election threshold and a history of socio-religious compartmentalization. In the past two decades, traditionally bigger parties have seen their electorate shrink, party support has become more and more volatile. At present there are 13 parties in parliament. The largest party in parliament, the VVD, only obtained 21,3% of the votes (gaining 33 out of 150 seats) in the 2017 parliamentary elections.

[2] In 2002, the Lijst Pim Fortuyn and Leefbaar Nederland together obtained 18,6% of the votes on the wave of support for Pim Fortuyn. See below.

[3] See the FvD’s website.

[4] The idea of online denunciation was not new: in the past, Geert Wilders’ PVV established several hotlines – including one where citizens were supposed to register inconveniences caused by East Europeans, and another to report "street terror" by the immigrant youth. These are effective media stunts.

[5] Stokmans and Heck, "Wie is deze ‘belangrijkste intellectueel van Nederland’?"

[6] From 2010-2012, the PVV supported a minority government of VVD and CDA. This government however resigned after the PVV withdrew support in disagreement over planned austerity measures, with both VVD and CDA blaiming Wilders for the failure of negotiations.

[7] Thierry Baudet in Powned, 17 December 2015.

[8] Ipsos, PS19. Verkiezingsonderzoek Ipsos in opdracht van de NOS. Amsterdam, 1 April 2019, p.19

[9] Ibid., p. 17.

[10] Ibid., p. 13.

[11] Ibid., p. 8.

[12] Maarten Huygen and Rik Wassens, "Vooral mannen kiezen voor Forum voor Democratie." In: NRC, 21 March 2019.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Jan Hoedeman, "Is Pim 2.0 nu opgestaan?" In: Het Parool, 23 March 2019.