Defining neoliberal efforts merely as market radical is misleading. The dynamic and diverse sphere of neoliberal actors, both worldwide and on a European level, makes it necessary to abjure simplistic reductions when looking at neoliberal networks. This applies in particular against the background of current post-Covid struggles.

It has been popular since the global financial crisis in 2008 again to think of neoliberalism as a terminally failed project (‘zombie ideas’), and accordingly to present the current period as an interregnum to post-neoliberalism. Less than a decade after the great crisis of both financialised global capitalism and neoliberalism, the pandemic has brought economic activity to a standstill once again and social systems are on the verge of collapse in many countries. Unlike the financial crisis ten years ago, the present crisis can be seen as a result of an external shock. But the impact of the virus also reflects the poor state of the public health system in many countries adversely affected by decades of austerity and the neoliberal priority of economic efficiency and profitability. The failure of the great powers to meet the global challenge of the pandemic by coordinating vaccine development and distribution demonstrates another shortcoming of the orientation to competitiveness. Instead of joining forces to meet a global challenge under the roof of the United Nations, leading countries and regional blocs are engaging in imperialist vaccine rivalry and health nationalism. Certainly, the neoliberal transformation of welfare state capitalism correctly deserves blame for the growing problems of the destruction of the living environment, growing social inequality and crumbling social infrastructures (Goldman 2005, Malm 2020, Patel and Moore 2017).

Alas, we will have to await the further unfolding of the multiple crises to know if we can indeed speak of a (terminal) crisis of neoliberalism. More likely – and not for the first time – we may live through crises in neoliberalism rather than leaving neoliberalism behind:One could think of the “pink tide” of left-wing governments from Argentina to Bolivia in Latin America during the commodity boom of the 2000s followed by the turn to authoritarian neoliberalism (Plehwe and Fischer 2019). Or the claims made by “New Labour” to go beyond neoliberalism in the late 1990s in Europe only to extend neoliberal approaches even further in the sphere of labour policy (“activation”, self-employment at the expense of lower benefits for shorter periods of time).

In order to comprehend controversies and struggles post-Covid it is important not to fall into the trap of attacking a neoliberal strawman, the easy to debunk misrepresentation of neoliberalism as market radicalism and anti-étatism. Although Pierre Bourdieu (1998) deserves much credit for his efforts to fight the “neoliberal invasion”, to defend the social and to direct attention to neoliberal authority, his presentation of neoliberalism as ‘pensée unique’, the “only thought authorised by an invisible and omnipresent opinion police”, as Ignacio Ramonet put it, (Ramonet 1995) needs to be seen as problematic and possibly misleading. Like the neoliberal claim of ‘TINA’ according to which there is no alternative to privatisation and marketisation, the claim that ’there is only one neoliberalism’ has not been helpful in recognising neoliberal parties and programmes. Although a neoliberal core does exist, market radicalism turns out not to be an accurate way of summing up neoliberal efforts to protect property rights and to secure market relationships, which requires control of the state and readiness to compete with alternative ideologies in many areas of public policy. Generalisations like pensée unique are difficult to maintain in light of the diversity of neoliberal intellectuals nor do they hold up to historical scrutiny. Much like competing ideologies, the evolution of neoliberalism has been driven by the diversity and versatility of neoliberal actors and agencies. Simplifying neoliberalism in this way also makes it difficult to assess the relative influence exerted by neoliberal ideas and social forces in various arenas, both national and international, such as the EU.

Three future ideal-type scenarios can be distinguished to assess developments in response to the strong political reactions to the Corona pandemic: first, a strong counter-movement managing once again to defend the status quo ante crisis at evidenced by the austerity 2.0 policies after the global financial crisis; second, a selective departure from the prerogatives of austerity capitalism in specific policy areas like public health and public institutions, e.g. an ongoing development of somewhat more progressive European public finance; third, a combination of progressive changes and a lasting momentum of initiatives for greater social equality and solidarity of people and nature within and across borders – the great transformation beyond the Green Deal.

With regard to neoliberal forces they will be among the key actors trying to accomplish outcomes a), surprisingly they may be frequently found to be among those who shape outcome b) and they will certainly belong to the most stubborn and steadfast opponents to outcome c). The real type developments will nowhere conform to the ideal types, always oscillating somewhere in between. In order to understand the utility of individual reforms and trajectories, ideal types do nevertheless provide guidance.

How can we examine neoliberalism in order to appraise the actors involved in political projects and assess the outcomes of policy conflict? Contrary to those who believe organised neoliberals are akin to a conspiracy, neoliberals can be studied much like other social forces, possibly better in terms of international dimensions due to their proclivity to transnational networking inter alia in associations like the Mont Pélerin Society (MPS) or think tank networks like the Atlas Economic Research Network (for the former see Plehwe and Walpen 2006, Mirowski and Plehwe 2009, for the latter see Djelic and Mousavi 2020). These networks of intellectuals, organisations – mainly, but not only think tanks – and ideas allow observers to follow neoliberal activities and conversations in a) all the different countries and b) across many policy areas.

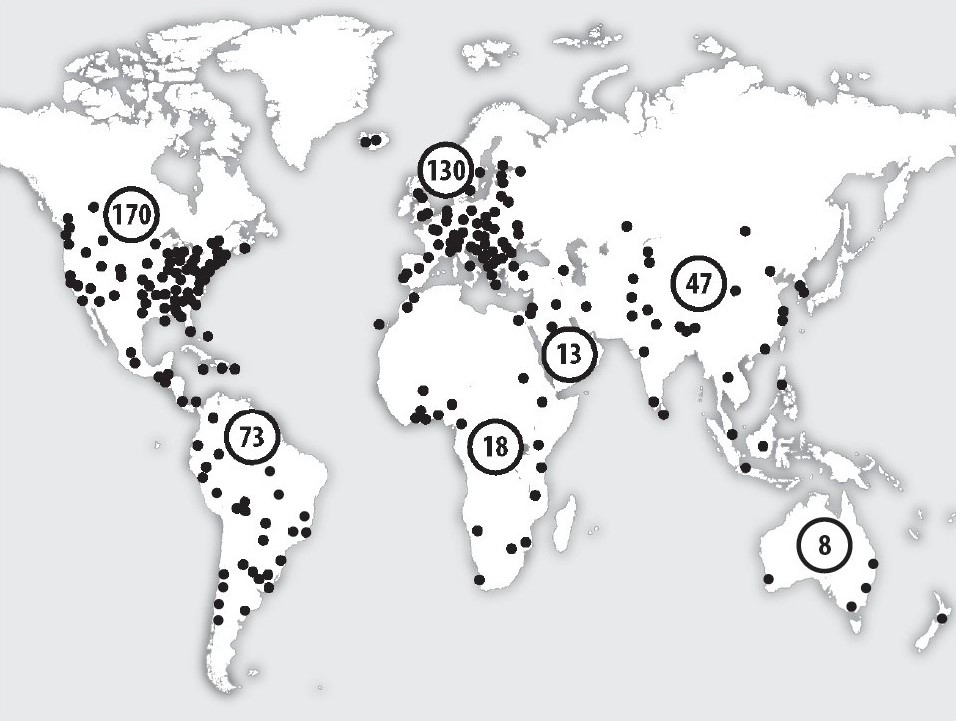

The following graph shows the global distribution of members of the Atlas Economic Research Network. It is easy to see that major efforts have been made to develop a presence in the Global South in addition to the heartland of Europe and the United States. At the same time, it is clear from the numbers that the presence of neoliberal think tanks is notably greater in Latin America (compare Djelic and Mousavi 2020 for more details). But Atlas is not the only neoliberal game in town. Much like members of the MPS founded by Hayek and others in 1947, neoliberal networks can serve as a proxies to identify additional neoliberal intellectuals – board and staff members of think tanks can be studied with an eye to allies and friends in academia, business, politics, civil society, or the media (see Plehwe, Walpen and Neunhöffer 2006).

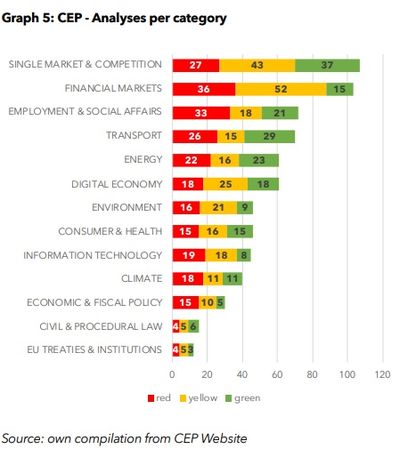

A useful way to learn about neoliberal assessments of European legislation is provided by the Centre for European Policy (CEP) in Freiburg, Germany. Founded in 2005, the think tank has become a major resource for neoliberal European policy making. CEP experts examine all European legislation considered relevant in many policy areas to evaluate agendas and proposals from a normative neoliberal perspective. From 2006 until 2019 CEP published 676 documents of various types and content. The following graph shows the distribution of CEP policy papers in different policy areas, and the broad assessment expressed with the traffic light system, with red representing rejection, green endorsement, and yellow neither of these two.

Source: Djelic and Mousavi 2020, p. 261,

compare closer analysis available online hdl.handle.net/10419/215796

The rather large number of red lights and the considerable amount of yellow lights suggest there is quite a strongly felt need on the side of neoliberals in the EU for debate and influence-peddling with regard to the direction of European policy-making. The red and yellow marks attached to individual legislative proposals will reliably indicate policies that are likely to be popular on the centre-left wing of the political spectrum.

Of course, the large number of red-light warnings expressed in neoliberal assessment does not mean that the EU has suddenly become a progressive universe. The many green lights indicate support for numerous pieces of legislation. More importantly, many left-wing objectives are prominent in terms of their absence from the European legislative agenda. But it is nevertheless noteworthy to see how many EU legislative items are debatable if not disliked from a (predominantly German in this case) neoliberal perspective.

Looking at the neoliberal networks over time reveals moments of struggle and crisis. During the 1950s, neoliberal universalists (like Ludwig Erhard and Wilhelm Röpke) opposed European integration whereas neoliberal constitutionalists (like Hayek and Mestmäcker) appreciated the opportunity to tie national legislators to supranational economic norms (Slobodian 2018, chapter six). In the early 1960s Röpke and his allies clashed with Hayek and his friends on the content and purpose of neoliberal organisation.

by Moritz Neujeffski;

Source: Günaydin and Plehwe 2020,

compare a closer analysis at: The Neoliberal Legal Turn

Röpke was firmly committed to a version of conservative neoliberalism and anti-communist political activism while Hayek explained why he did not consider himself a conservative and wanted the slate of intellectuals to focus on academic and ideological struggles, refraining largely from open political statement (Walpen 2004). During the 1980s, Mises’s student Murray Rothbard split from MPS members Koch and Crane at the CATO Institute to set up the Mises Institute in Auburn (USA). Rothbard accused the neoliberal mainstream of elitism and mainstreaming and sought a radical alliance on the more extreme right wing. After flirting with the anti-militarist left in the 1960s and 1970s, Rothbard turned to so-called paleo-conservatives who supported private militias and secession to forge an alliance with his own group of paleoliberals. Contrary to neoconservatives, the alliance continued to oppose military expansionism. In 1992, Rothbard called this strategy right-wing populism (Rothbard 1992, compare Wassermann 2018). In 2006, Rothbard disciple Hans Hermann Hoppe founded the Property and Freedom Society based on the MPS model, providing an umbrella for sprawling Mises Institutes around the globe. Both the Atlas Network and the Property and Freedom Group grew strongly after 2009 suggesting that neoliberals and their financial supporters did not give up their struggle during the global financial crisis.

The Mises-Rothbard-Hoppe split has reintroduced the term “paleoliberal” to the debate. Originally used in a pejorative way by Röpke and Rüstow to attack the orthodox views of Mises and to a lesser extent Hayek, Rothbard’s founding partner Llew Rockwell embraced the term to proudly profess purity and commitment to a radical anti-state perspective extending to the field of military and security. Within the neoliberal mainstream we can identify a right-wing mosaic of positions reflecting different traditions and thought collectives, inter alia ordoliberalism, Virginia public choice, Chicago monetarism and law and economics, the international outlook of the Geneva school, the neoliberal economic geography founded in Kiel, or the recently discovered Catholic neoliberalism of the Navarra school. Sometimes quite incompatible streams coexist peacefully, sometimes not. In 2015, the German Hayek Society broke apart. Two groups of members – close to the German mainstream parties CDU (conservatives) and FDP (liberals) – left the German Hayek Society because they did not manage to purge the socially more conservative and neo-nationalist members with strong affinities to the right-wing challenger party AfD. The moderate neoliberals banded together in the new Network for Constitutional Economics and Social Philosophy (NOUS). Radical Mises Institutes and moderate groups like the NOUS network still intermingle both in MPS and Atlas network circles, but they clearly diverge on many questions as, for example,the European neoliberals did on the question of Maastricht and monetary union (Slobodian and Plehwe 2019).

Diversity can be a handicap, but it can also lend strength and create opportunity. There are plenty of neoliberal think tanks and pundits ready to return to austerity capitalism after Covid, eager to demonstrate the temporary character of concessions made in the face of the pandemic. Other neoliberal circles consider the present moment similar to the crisis of liberalism in the 1930s. In deliberate allusion to the foundational event of global neoliberalism, the Colloque Walter Lippmann in 1938 in Paris, the NOUS network recently organised another Lippmann conference.

Karl Mannheim’s study of the conservative ideology clarified that world views need to adapt to new challenges and to integrate elements of successful challengers. This insight helps to explain the permutations of neoliberal ideas within social democratic and conservative bodies of thought. The insight is also important to explain why neoliberals will be part of the conversation with regard to the above-mentioned “second outcome” scenario, which is a partial departure from austerity capitalism in an effort to address the public health and climate crises. But orthodoxies can also find allies and purpose in fighting rearguard battles to secure property rights in the fossil sector, for example. Due to the circumstance of the time, tensions within the neoliberal networks are likely to increase, which should not lead observers to again prematurely dismiss the productive universe of neoliberal ideas and the social forces and constituencies sustaining them.

References

Pierre Bourdieu (1998): Acts of Resistance Against the Tyranny of the Market. New York: The New Press.

Marie Laure Djelic/Reza Mousavi (2020): How the Neoliberal Think Tank Went Global. The Atlas Network, 1981 to the Present. 257-282. In: Dieter Plehwe, Quinn Slobodian and Philip Mirowski (Eds.): Nine Lives of Neoliberalism. London: Verso.

Michael Goldman (2005): Imperial Nature. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Kardelen Günaydin/Dieter Plehwe (2020): The Neoliberal Legal Turn. Online: thinktanknetworkresearch.net/blog_ttni_en/the-neoliberal-legal-turn/

Andreas Malm (2020): Corona, climate, chronic emergency. War communism in the twenty-first century. London: Verso.

Philip Mirowski / Dieter Plehwe (Eds.) (2009): The Road from Mont Pèlerin. The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Rajeev Charles Patel / Jason Moore (2017): A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things. A Guide to Capitalism, Nature, and the Future of the Planet. Oakland: University of California Press.

Dieter Plehwe / Karin Fischer (2019): “Continuity and Variety of Neoliberalism. Reconsidering Latin America’s Pink Tide”. In: Revista de estudos e pesquisassobre as Américas, Vol. 13, No. 2, p. 166-202.

Dieter Plehwe, Bernhard Walpen and Gisela Neunhöffer (Eds.) (2006): Neoliberal Hegemony. A Global Critique. London: Routledge.

Ignacio Ramonet (1995): La pensée unique. Le Monde diplomatique. https://www.monde-diplomatique.fr/1995/01/RAMONET/6069 (last accessed April 28, 2021).

Murray Rothbard (1992): Right wing populism: A strategy for the paleo-movement. Rothbard Rockwell Report 3 (January) 5-14.

Quinn Slobodian (2018): Globalists. The end of empire and the birth of neoliberalism. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Quinn Slobodian/Dieter Plehwe (2019): “Neoliberals against Europe”. In: William Callison/Zachary Manfredi (Eds.): Mutant Neoliberalism. Market Rule and Political Rupture. New York, NY: Fordham University Press, S. 89-111.

Bernhard Walpen (2004): Die offenen Feinde und ihre Gesellschaft. Hamburg: VSA Verlag.

Janek Wasserman (2018): The Marginal Revolutionaries. How Austrian Economists Fought the War of Ideas. New Haven: Yale University Press.