Between 17-21 July the heads of EU Member States (MS) met together in Brussels and spent as much time haggling over the ‘development plan’, which is designed to stabilise economies weakened by the coronavirus, as over the next Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF). What should we make of their decisions?

It has to be acknowledged that one of the great economic dogmas of the EU has actually been thrown overboard. For the first time, it was decided that the EU would be permitted to go into debt. In times when interest rates are so low, raising money to invest in relevant projects is a clever move. All the same, with regard to the whole EU there will be a macroeconomic stimulus amounting to 0.7% of the EU’s GNP for the next three years.

If this is indeed the case, why did MEP Martin Schirdewan, the Co-Chair of the GUE/NGL group in the European Parliament (EP), talk about a “black day” for Europe? – Because essential issues have been completely ignored.

What are these great unsolved issues?

1. Contrary to all claims, there is still no clear link between receiving EU aid and compliance with the fundamental principles of the rule of law;

2. The ‘discounts’ that the “four States lacking in solidarity” (the Netherlands, Austria, Denmark and Sweden) and the supposedly “good” Germany have secured for another seven years on their EU contributions will be largely at the expense of France and Italy.

3. It is already clear that every country that receives funding from the EU will, sooner or later, be subject to neo-liberal obligations; in his article, Yanis Varoufakis named the ‘elephant in the room’ that nobody wanted to talk about: the policy of cutbacks. He rightly stated that the nonsensical Stability and Growth Pact had only been suspended. The Vice-President of the EU Commission, Valdis Dombrovskis, has already announced his desire to start a discussion on the subject this autumn, to talk about when the EU can finally instruct its Member States to comply with this pact again.

4. There has been a huge number of cutbacks that has in part erased the most promising EU programmes.

To what extent do the MFF and the development plan help the Member States most affected by the coronavirus, such as Italy?

First of all, the Council’s decisions of course mean that the EU will (collectively) go into debt, to the tune of EUR 750 billion. Italy will be responsible for 13% of this – while having a national debt of approx. 160% of GDP (2020). If we offset this new debt against the grants that Italy will receive from the development plan, Italy will receive a net figure of EUR 30 billion for 2021-23. By way of comparison: Germany will support the East German coal regions, where 16,000 jobs depend on the coal industry, with a package worth EUR 20 billion.

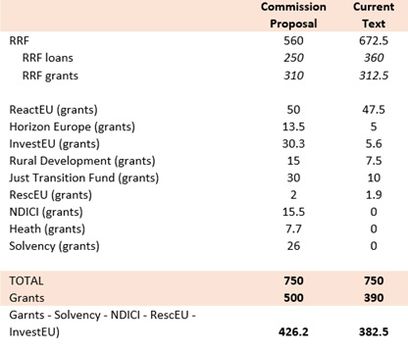

The negotiations resulted in a poor balance of interests between the four States lacking in solidarity that simply want to cut back and those States that need swift, direct aid. The result was that the subsidies increased slightly from EUR 310 billion to EUR 312.5 billion, although the sums intended for forward-looking projects within the recovery plan, which were meant to top up normal EU budgetary programmes, were in part completely abandoned.

Source: Silvia Merlers , Head Of Research – Algebris Policy & Research Forum

Breakdown of the new NextGenerationEU instrument aiming at recovery & resilience in the face of the pandemic and coming on top of the MFF programmes (except for RFF, React-EU and Solvency, which are specific to NextGenerationEU), — as originally proposed by the EU Commission (1st col.) then agreed by the participants during the 17-21 July European Council (2d col.)

Notes : RFF: recovery and resilience facility (the main component of the NextGenerationEU instrument). React-EU: Recovery Assistance for Cohesion and the Territories of Europe; Horizon Europe: Research; InvestEU: programme to boost jobs and growth (replaces the EFSI or "Juncker plan"); Rural Development: agriculture; Just Transition Fund: ecological transition; RescEU: disaster risk management & civil protection; NDCI: Neighbourhood, development and international cooperation instrument; Health: EU4Health; Solvency: recapitalising companies put at risk by the pandemic crisis.

The ‘Rural Development’ programme, for example, important for climate policy, has been halved; the ‘Just Transition Fund’ curtailed by two thirds; and the ‘Solvency Support Instrument’, which is designed to support small and medium-sized businesses (SMEs), is to be discontinued altogether in the biggest economic crisis. With breathtaking, unparalleled audacity, the health programme has also been completely cancelled. Among other things, the plan included the creation of reserves of medical supplies and training health professionals for deployment across the whole of the EU so that, in an emergency, they could be placed where they were needed (‘EU4Health’).

Although our biggest issue remains the level of CO2 emissions, which is still far too high, things also look bleak on the climate policy front. Even if the goal were set at spending 30% of the MFF and development plan funds on protecting the environment, this would amount to just EUR 547.2 billion for the next seven years. According to estimates by the Commission, however, we require EUR 1.46 trillion in investment each year in order to achieve the climate goals by 2030. If we now consider the risk of reintroducing the so-called Stability and Growth Pact with its cutback requirements, the situation is clear: the MS and the EU itself will never have the financial means to meet even the minimum goals of a sustainable way of doing business.

What are the solutions? What must the left fight for in Europe?

In the short term, individual MS must form a ‘coalition of the willing for Eurobonds’ and thus go to the financial markets. This is the only way to circumvent neo-liberal EU requirements. In the medium term, it will require EU treaty changes. This is the only way to ensure that the EU has the permanent right to incur debt and maintain a ‘normal’ central bank in which all participating countries can have a say over monetary policy. There must also be a shift in power in favour of the European Parliament (EP). The Parliamentarians in the EP are far from being morally superior delegates, but it is they who have to grapple with their party colleagues from other countries in political discussions, which allows them to keep other countries in mind. The EP must ultimately become the central hub for the political debate – with effective control features applied too.

The results of the Council meeting are too multifaceted to suggest an easy answer. On one hand, the 27 Member States have actually quickly put together an aid package of EUR 750 billion. On the other hand, this is a ‘no-brainer’ when measured against the real challenges. Again, it is the MS that have been strengthened rather than the democratically legitimised EP. Despite the big fuss, the decisions of 21 July have not strengthened collaboration in the EU.