The German political system is experiencing a major change[1]. This has already been illustrated by last year’s parliamentary elections, the difficulties in forming a government, government crises and now, also, the results of the state elections held in Bavaria and Hesse. An Overview.

The parties of the grand coalition have each lost more than 10% of their voters. For the social democratic SPD, this is the equivalent of losing half of their supporters (1.1 m voters), more than 40% of their supporters in Hesse (391,000 voters). Both state elections were heavily influenced by the coalition parties’ actions and the way they treated one another.

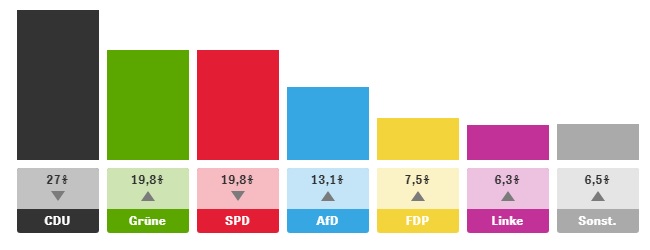

While in the 2017 parliamentary elections, the governing parties still reached 53% of the vote, one year later, they managed to achieve only 46.9% (CSU: 37.2%, SPD: 9.7%), and in Hesse 46.8% (CDU: 27%, SPD: 19.8%). For the first time, the SPD fell below the 10% mark in a West German state and scored below its hitherto lowest result of 9.8% in the Saxony state elections of 2004.

Also, the CDU/CSU has lost voters, mainly to two other parties. On the right, the AfD has become a serious competitor, while an increasing number of conservative-liberal or Christian voters chose to vote for the Greens this time. This means, that the government – and especially the SPD – is losing its democratic legitimacy, and the governing parties have to deal with increasing pressure to implement fundamental changes.

Bavaria

|

Political party |

2008 |

2013 |

2018 |

Compared to 2013

|

|

Conservatives (CDU/CSU) |

43.4% |

47.7% |

37.2% |

-10.5% |

|

Social Democrats (SPD) |

18.6% |

20.6% |

9.7% |

-10.9% |

|

Free Voters |

10.2% |

9.0% |

11.6% |

+2.6% |

|

Greens |

9.4% |

8.6% |

17.5% |

+8.9% |

|

Right-wing populists (AfD) |

|

|

10.2% |

+10.2% |

|

Liberals (FDP) |

8.0% |

3.3% |

5.1% |

+1.8% |

|

Radical Left (DIE LINKE) |

4.4% |

2.1% |

3.2% |

+1.1% |

Hesse

|

Political party |

2009 |

2013 |

2018 |

Compared to 2013 |

|

Conservatives (CDU/CSU) |

37.2% |

38.3% |

27.0% |

-11.3% |

|

Social Democrats (SPD) |

23.7% |

30.7% |

19.8% |

-10.9% |

|

Greens |

13.7% |

11.5% |

19.8% |

+8.3% |

|

Right-wing populists (AfD) |

|

4.1% |

13.1% |

+9.0% |

|

Liberals (FDP) |

16.2% |

5.0% |

7.5% |

+2.5% |

|

Radical Left (DIE LINKE) |

5.4% |

5.2% |

6.3% |

+1.1% |

The consequences for the governing parties

Angela Merkel’s announcement not to put forward her candidacy as CDU chairwoman represents the first reaction. Her potential successors include, amongst others, Friedrich Merz, a business-oriented and neoliberal politician who emphasises the concept of the ‘German core culture’ (a monocultural vision of German society) and distances himself from Merkel’s approach to refugees in 2015. He calls for clear immigration and integration rules.

Before discussing any further consequences, the CSU wants to form a state government with the Free Voters in Bavaria and await the election of their frontrunner for the upcoming EP elections. Also, the Social Democrats would not benefit from an immediate resignation from government without any credible schedule for reforming German social democracy or re-electing a party chairperson without rejuvenating their party programme and strategy. Merely introducing new leading personnel, such as Schulz and subsequently Nahles in 2017, is not enough in order to credibly demonstrate the party’s renovation.

And the opposition?

After the recent state elections, the AfD will be present in all German state governments, even though its results remained below expectations with 10.2% in Bavaria and 13.1% in Hesse. They are, however, double-digit results, which up until now had only been achieved in Eastern German states. In Bavaria, a part of their potential voters opted for the Free Voters instead, who show a similar attitude regarding refugees, but use a less radical rhetoric. In Hesse, the AfD tried to reach conservative bourgeois voters and abstained from supporting its German nationalist wing. According to polls, 58% of the party’s voters share the opinion that the AfD isn’t distancing itself enough from right-wing extremist positions – which, however, is not perceived as an impediment to voting for them.

The Greens are the winners of this election, and not just because they are the clear opponents of the AfD. They positioned themselves as a liberal bourgeois counter proposal to the CSU and as a political antithesis to the new developments on the right of the political spectrum. In both states, the Greens have become the second strongest political force with 17.5% in Bavaria and 19.5% in Hesse. The Greens won as a unified force with clear positions regarding climate, environmental, European, and refugee and asylum policy, which isn’t necessarily connected to their real everyday political work in various state governments. Their political approach, which is based on substantive work and specific projects, and uses an inclusive political language and a rather anti-populist political style, clearly differed from the bickering between the parties of the grand coalition and the AfD’s hate-inciting political style – even though the latter remained less overt during this recent election campaign than in previous ones.

The Greens are dealing differently with the topic of the future. Amongst others, they are addressing problems connected to climate change, which have already been manifesting for some time. They are voicing their concerns regarding democracy and talking about the ‘reproduction of sociality’ as a specific and topical challenge. They are not discussing ‘big concepts’, but are focusing on feasible steps and assuming responsibility. In Hesse, they are connecting their governing responsibility with the pragmatism of a down-to-earth party of the ‘democratic centre’, which advocates an open and tolerant society, for a humane asylum policy. Therefore, in Bavaria, they took to the streets to demonstrate against the tightened police act. The Greens didn’t only win in the big cities, but also managed to convince voters in the smaller cities and rural areas by addressing topics such as housing, sustainable development, land use, transport and mobility. Unlike DIE LINKE, the Greens aren’t only performing well in the big cities. They reached more than 10% in all regions of Bavaria and Hesse, and between 20 and 30% in the big cities. They addressed old-age poverty and the necessity of a guaranteed child allowance, the obvious problems in the care sector, and the lack of health institutions especially in rural areas. In Bavaria as well as in Hesse, they had the right personnel to authentically represent the party’s course. Also, they were backed by the Greens’ federal level.

Looking at the substantial gains they received from various political camps, it remains an open question whether the Greens will evolve into some new kind of popular party. It is clear, however, that following their current strategy, they will become a challenge for DIE LINKE as well.

DIE LINKE has managed to increase its share of the vote by 74%; more than 180,000 Bavarians cast their vote for them. Still, a result of 3.2% wasn’t enough to enter the state parliament. In Hesse, DIE LINKE also managed to improve its result. It achieved 20,000 additional votes and, with its 6.3%, will be represented in the state parliament. These results, however, remained below their expectations. The reasons for this include the fact that, unlike the Greens, DIE LINKE seems disunited on a federal level – especially in the area of refugee and migration policy – even though it has been reaching very specific party congress resolutions. DIE LINKE has strengthened its profile as a party of social justice and is perceived as competent in the areas of social justice, affordable housing and family policy. However, the party reaches voters in the urban areas and big cities to a much higher extent (even managing to achieve double-digit results) than voters in rural areas. It is also the urban areas where specific projects aimed at social justice have been implemented. Their ‘counterparts’ tailored to smaller cities and rural areas have yet to be developed further. A precondition for that, however, is represented by active local party branches. In places where DIE LINKE is well-established and active, it achieves good, or even extremely good, results. This means that the question of organisational development must be answered regarding these rural areas too.

At the same time, DIE LINKE’s strengths must be developed further. In Hesse and Bavaria, DIE LINKE is a reliable partner for social movements. These include global justice movements, protests against the ECB’s austerity policy, against the G20, against large-scale projects which damage the environment, such as the expansion of the Munich airport, and against the tightened police act in Bavaria. It advocates an open and tolerant society, affordable housing, widespread access to care and medical institutions, and education for everyone. DIE LINKE is locally active in welcoming initiatives for the integration of refugees. If, however, the party’s representation on a federal level sends mixed signals, it will fail to reach a part of its potential voters in the future too.

[1] The following remarks are mainly based on analyses of the state elections in Bavaria and Hesse by Horst Kahr. See files attached;

Die Wahl zum 18. Bayerischen Landtag am 14. Oktober 2018 Wahlnachtbericht und erster Kommentar (German); source: https://www.rosalux.de/fileadmin/rls_uploads/pdfs/Themen/wahlanalysen/2018-10-14_LTW_BY_WNB.pdf

Die Wahl zum 20. Hessischen Landtag am 28. Oktober 2018 WAHLNACHTBERICHT UND ERSTER KOMMENTAR (German); source:

https://www.rosalux.de/fileadmin/rls_uploads/pdfs/Themen/wahlanalysen/2018-10-29_Ka_LTW18_HE_WNB.pdf

Traducción: José Luis Martínez Redondo