In the face of current challenges, the EU is at a crossroad. Whether, as a consortium of strong nation-states, it develops into a new type of free-trade zone or intervenes in the future as an independent actor in global conflicts will strongly depend on the conservative forces that constitute the single most politically influential force in the EU.

The conservatives have a relative majority in the three central EU institutions: In the European Council they are represented by more than ten heads of state or government; they have ten members of the European Commission, including its president and the key departments of economy, trade, transport, and the internal market, which in coordination with the EU Council can push forward on strategic precedent-setting initiatives. In the European Parliament the conservatives are organised in two groups: the European People’s Party (EPP), which bring together Christian Democratic, bourgeois conservative, and national conservative parties; and the European Conservatives and Reformists Group (ECR), which was founded in 2009 under the leadership of Britain’s Conservatives and Poland"s national conservative Law and Justice party (PiS). It contains EU-sceptical and, in part, right-wing populist parties.

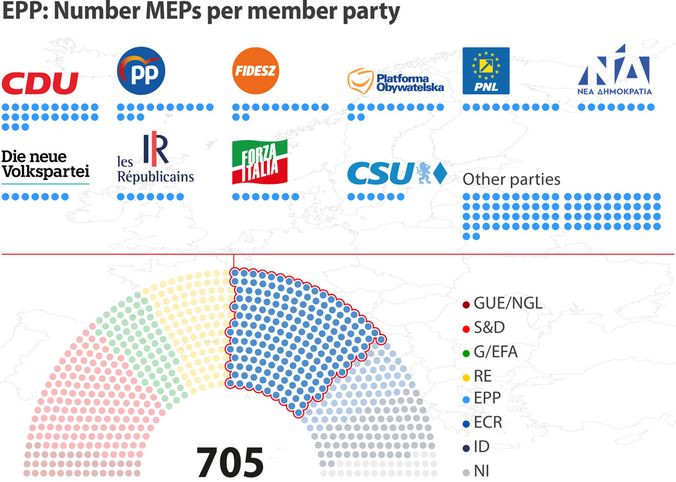

The EPP‘s strongest parties are Germany’s CDU with 23 MEPs, Spain’s People’s Party (PP) with 13, and with 12 MEPs each Poland’s Civic Platform (PO) and Hungary’s FIDESZ (out of 187).

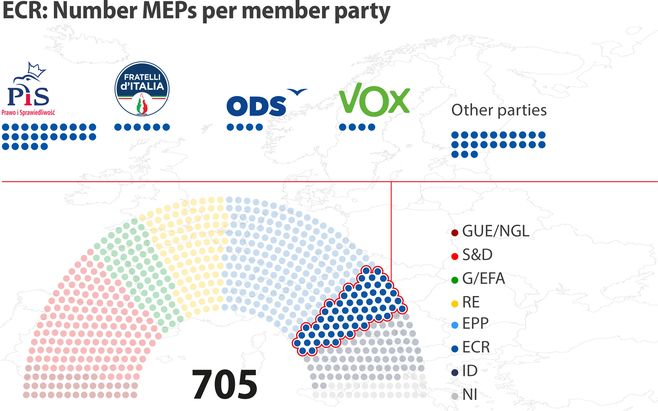

GUE/NGL: European United Left / Nordic Green Left (radical left); S&D: Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (social democrats); G/EFA: Greens/European Free Alliance; RE: Renew Europe Group (liberal); EPP: European People’s Party (conservative); ECR: European Conservatives and Reformists (right wing); ID: Identity and Democracy (right wing); NI: Non-Inscrits (non-affiliated Members);

Note: Including one Spanish seat still vacant (after the re-distribution of seats following Brexit) (20/6/2020).

Source: Sanja Kaltenbrunner-Jelic/transform! europe

In the ECR Poland’s PiS is predominant with its 25 MEPs (out of 62). Trailing at a distance behind it are Italy’s and Spain’s extreme right parties Fratelli d’Italia and VOX, as well as the Czech ODS.

Source: Sanja Kaltenbrunner-Jelic/transform! europe

The 1999 EP elections made the EPP – which at the time was still in coalition with the European Democrats (ED) group led by Britain’s Tories – the strongest group for the first time. At that point it garnered 37 per cent of seats with 295 MEPs. After Brexit and the redistribution of the vacated seats, the EPP has 187 MEPs. The second conservative group, the Euro-sceptical national conservatives of the ECR, now only has 62 MEPs, making it the EP’s second smallest group.

This evolution has direct impact on possible majority constellations. In the 2019 elections, the two large groups, the conservatives of the EPP and the social democrats of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats group (S&D) – both strongly influenced by their respective German member parties, the CDU/CSU and the SPD – received, for the first time, less than 50 per cent of MEPs and could thus no longer act like an informal ‘grand coalition’, as they had previously done. Both groups lost almost 20 per cent of the MEPs they had from the 2014 elections. In the case of the EPP the loss, in relation to 2009, even exceeds 30 per cent. The EPP’s collapses have occurred throughout the EU, but their extent is ultimately determined by the changes in the party landscapes in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and Poland. In the EP’s decision-making processes these losses can no longer be compensated – as they often were in the past – by the Euro-sceptical national conservatives of the ECR, for their influence too has declined over the years. The share of the nationalist and anti-European parties to the right of the ECR has more than doubled. This growth is also due to realignments among the groups. Thus, in 2019 MEPs from parties such as the Danish People’s Party, Germany’s AfD, as well as the True Finns have given up their ‘hideout’ in the ECR and formed a notably strengthened extreme-right group under the name Identity and Democracy (ID). This shakeout among the groups is still not over and could possibly threaten the ECR’s existence.

As a result, the constellation of forces in the European Parliament is characterised by three tendencies: first, the conservative EPP together with its longstanding partner, the S&D, is no longer capable of its own parliamentary majority; second, the two pro-European party families whose relative weight has increased, the liberals and Greens, exert strong pressure for a deepening of the integration process within the EU; and, third, the nationalist, anti-democratic, and anti-European parties have gained significant influence in the Parliament.

European conflict lines and new cracks

Against this background we can discern three possible scenarios for the EU’s further development: First, a modified ‘more of the same’ with clear rightward shifts, especially in migration and refugee as well as security policy; second, the development of strong national states into a free-trade zone; or, third, the EU’s evolution to become an independent actor economically, politically, and militarily.

If the conservatives and social democrats hold true to their principle of not cooperating with the nationalist right-wing extremist ID group, it is equally improbable that they can form a majority with the party families nearer to them. Concretely, the numbers are there neither for a conservative-liberal-Green majority nor for a conservative-national conservative-nationalist alliance. The conservatives can only produce a majority in alliance with the social democrats plus another party family.

Parallel to the repositionings between the groups are the conflicts within them. Thus the liberal conservatives, who like Luxembourg’s conservatives favour a deepening of the EU along the lines of Marcron’s economic liberal ideas, stand in opposition to those conservatives who like the CDU in Germany reject a further communitarisation of financial and economic policies, of asylum and refugee policy, and above all a social convergence of the EU countries. On the other hand, the liberal conservatives support the latter’s proposals for a European army. This also applies to the national conservatives of the ECR, who like Poland’s PiS insist on the national sovereignty of their states and are fundamentally sceptical of an expansion of EU community policies but at the same time support the creation of a European army as long as it is not in competition with NATO.

This concrete point of conflict makes it clear that each different view of the role of the EU, of international developments or of global actors such as the US, China, or Russia is strongly shaped by factors such as national history, the size and geographical location of countries, and their political and economic position within the EU. Another important factor is whether the state"s role is that of a ‘central state’ or a country in the EU periphery, or whether its status is that of an EU money giver or taker. Clearly, ‘country interests’ repeatedly overlap the interests of the party families, are partly at odds with them, and promote or block Europeanisation. At the same time decision-making processes are additionally influenced by new kinds of inter-state EU-internal accords on the pooling of individual national interests. Thus, for example, the Visegrád countries ‘collectively’ reject any European regulations of immigration and refugee policy; the Group of Sixteen, to which the five Balkan countries, eleven Central and Eastern European EU countries, and now Italy belong, formulate their own initiatives in China policy; the countries of the so-called ‘Hansa Group’, which see themselves as ‘good housekeepers’, reject any increase of the EU"s budget and a relaxing of the European Stability Mechanism, or a communitarisation of state debt. The arenas of conflict are becoming more complex. The fault lines within the EU and also within the family of conservatives are becoming more differentiated. This means that they have at the same time to deal with those anti-European nationalists who are demanding that the influence of European institutions be diminished, who no longer want to abolish the EU but want to change it from inside out and develop it into a sealed fortress against refugees and immigrants.

Searching for solutions

With this, the conservatives of both groups are facing a dilemma: In many policy areas, there are different or even opposite positions among conservatives of both families. This applies to the relationship to China, Russia, and the US, militarisation and the construction of a European army, budget and agricultural policy, ecological reconstruction, including exiting from coal, emissions trading, the attitude towards nuclear energy, and not least the position on taking in refugees. At present, the strongest bond amongst conservatives is the question of securing the EU’s outer borders against flight and migration. As is visible in the crisis at the Turkish-Greek border, law, freedom, and prosperity are placed at the service of this goal and – in contrast to Germany"s ‘go it alone’ in 2015 – human-rights policy clearly subordinated to security policy. Thus in this question the distinctions that exist elsewhere between the conservatives and the spectrum of the partly ethnic-nationalist parties to their right are blurred.

The effects of a growing hermetic security concept to the detriment of considerations of human rights and democracy raise the question of the democratic substance of the EU and its Member States. But at the same time they call into question the fundamental conservative values of law and liberty, including market freedom – that is, the foundation of conservative values – and push the conservatives towards the extreme-right parties. This outlook on security emerging amongst conservatives can hardly offer answers to the current global challenges. What would be needed is a concept of security on whose basis the EU, as an independent globally active player, upholding European values, intervenes in global confrontations including those around the management of climate change, the worldwide spread of diseases, migration, and flight, and digital/social upheavals, developing for these purposes a new understanding of sovereignty as a national and European idea.

The relations of force in the European Parliament have made it necessary for the conservatives to approach not only the social democrats but also one of the other two ‘pro-European party families’. For the conservatives this could open up the possibilities of an ‘economic liberal" modernisation, which could in turn contribute to digitalisation, the strengthening of European institutions, and the development of new negotiation processes for qualified majorities. This would also serve for carrying out a ‘Green New Deal’. It would lead to new forms of cooperation with ‘changing majorities" in the European Parliament. In all of this, however, left parties at present have no function.

First published (with modifications) at: WeltTrends. Das außenpolitische Journal, 163/May 2020, 32 – 37.