Every sector of the economy has felt the impact of the coronavirus crisis, and car manufacturing is no exception. There are 12 million EU workers employed in the automotive industry, either directly in production or in parts manufacturing, and the sector accounts for 7% of the union’s GDP.[1] If we look at direct automotive employment

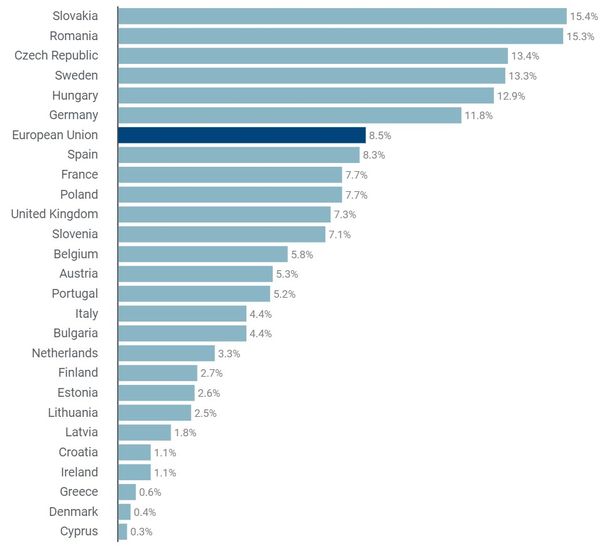

Every sector of the economy has felt the impact of the coronavirus crisis, and car manufacturing is no exception. There are 12 million EU workers employed in the automotive industry, either directly in production or in parts manufacturing, and the sector accounts for 7% of the union’s GDP.[1] If we look at direct automotive employment as a share of total manufacturing across a selection of EU member states, we can see just how significant the car industry is (see graphic, below).

The necessary restructuring of the sector will therefore impact millions of employees and have to contend with a well-organised car lobby. At the height of the crisis (25 March 2020), the European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA) called for the temporary suspension of stricter CO2 emission standards for passenger cars. This is in spite of the fact that transport accounts for a quarter of the EU’s total CO2 emissions and is the EU’s only sector to have actually seen CO2 emission growth in recent years.[2] It is thus obvious that this industry urgently needs radical change. If no action is taken, we will stand no chance of even slowing down global warming, let alone stopping it.

Share of direct automotive employment in the EU, by country (2017)

Source: European Automobile Manufacturers Association (ACEA), based on: Eurostat

But it is not only the ACEA that is standing in the way of a new beginning in the automotive industry; many employees also have little appetite for change. Germany’s largest trade union, IG Metall, for example, complained that the government’s stimulus package, announced on 3 June 2020, only included purchase premiums for electric cars and zero support for combustion engine models.[3] Understandably, IG Metall is concerned about potential job losses. In Slovakia, a country that relies heavily on car manufacturing, automation and e-mobility threaten 40% of jobs in the automotive sector, which could lead to companies exerting even higher pressure on their employees and employment conditions worsening even further.[4] In Slovakia, as of 1 June 2020, no aid has been agreed for the automotive sector – despite Volkswagen and Jaguar requesting help from the Slovakian government. Hungary is another country that has until now (as of 1 June) not granted any direct aid to the car industry, but has offered public guarantees for loans and subsidies for loan repayments. On 26 May 2020, France agreed an €8 billion rescue package for electric and combustion engine cars (including trade-in premiums) and an additional €5 billion loan to Renault.[5]

But even if we remove Covid-19 from the equation, the car industry globally has been in crisis for several years, its sales figures falling.[6] The industry was in need of urgent restructuring before the pandemic hit: a shift towards climate-friendly products was needed for the sake of the environment and to secure jobs. There is one supposedly ‘green’ solution to the automotive sector’s troubles that both EU politicians and the German government have been advocating: the electric car. In its proposal for a major recovery plan, the European Commission proposed investing in battery research alongside funding 1 million electric car charging stations across the EU.[7] In A New Industrial Strategy for Europe published on 10 March 2020, the European Commission announced that the European Battery Alliance would be expanded.[8] But the electric car is not as climate-friendly as it is often proclaimed to be: its manufacturing, particularly of the car’s battery and body, creates an enormous ‘ecological rucksack’. Depending on lifetime mileage and the energy mix, the difference between electric cars and combustion engine vehicles is negligible.[9] In terms of improving the overall environmental impact, for both types of vehicle, it makes sense to build small, lightweight, fuel-efficient cars, to use vehicles for as long as possible and to transport as many passengers as possible.[10] And let’s not forget: whether you are in an electric or a combustion engine car, road congestion is still unavoidable. Electric cars do not offer an answer to the lack of space that plagues our cities. What we need is an expansion of alternatives to cars, such as public transport, long-distance train travel, cycling and freight transport by rail. Rethinking transport this way could create thousands of jobs in various production sites across the EU. In Germany, for example, this could mean approx. 100,000 jobs in railroad vehicle construction, wagon and railcar manufacturing as well as maintenance works. An additional 100,000 employment opportunities would also be created in the development and production expansion of e-bus systems, small and dial-a-bus services, and specialised commercial vehicles, together with 100,000 new jobs in the production of cargo and e-bikes.[11]

We therefore need a complete redesign of the automotive sector, with a drive towards sustainable mobility. For this to happen, statutory provisions will need to be put in place and the state will also have to ensure proper funding is available to advance the development of public transport and long-distance rail travel. The German government coronavirus rescue package, however, features little in terms of support for German railways. A left-wing Green New Deal must not only ensure a rapid social and ecological transformation of car models; we must, in the medium term, also work to convert the car industry into a sector that favours more climate-friendly mobility, such as the production of vehicles for public and rail transport.[13] In order to make this a reality, climate movements and unions must come together, including at the European level, so that EU manufacturing bases cannot be played off against one another. The necessary alliances are already starting to take shape: for example, Students for Future are supporting German trade union ver.di’s fight for better employment conditions for public transport workers. It may just be one small step, but it is a start.

Notes

- European Sector Skills Council, Automotive Industry

- European Environment Agency, Greenhouse Gas Emissions by aggregated sector (08/06/20).

- Tagesschau, Thomas Kreutzmann: Die Wut auf die SPD in der Autokrise, 07/06/20

- Marianne Arens, ‘Changes in the car industry threaten Slovakian workers’, 13/02/2020, in: World Socialist Website.

- Latham & Watkins: PUBLIC FINANCE SUPPORT (STATE AID) GRANTED TO THE AUTOMOTIVE SECTOR

- Stephan Krull, ‘Autokrieg – Krise und Zukunft einer Schlüsselindustrie’, Sozialismus, 5/2017.

- COM, Europe’s moment: Repair and Prepare for the Next Generation, 27/05/2020, COM(2020) 456.

- KOM, Eine neue Industriestrategie für Europa, Brussels, 10/03/2020, COM(2020) 102.

- Electric vehicles from life cycle and circular economy perspectives, European Environment Agency, Report No. 13/2018, 57.

- PowerShift, Merle Groneweg and Laura Weis: Weniger Autos, mehr globale Gerechtigkeit

- Zeitschrift LuXemburg, Mario Candeias: ‘Der Mietendeckel der Mobilität’, Zeitschrift Luxemburg, May 2020

- Die Linke., Bernd Riexinger: Mobilitätswende und sozial-ökologische Transformation der Autoindustrie, 05/05/2020